Developers struggle with context switches

If you want to know what people are struggling with, look for the memes.

Jokes are rooted in consensus (or at least in a shared perception) so if you find a meme going around, chances are it’s describing a pain point that a group of people share.

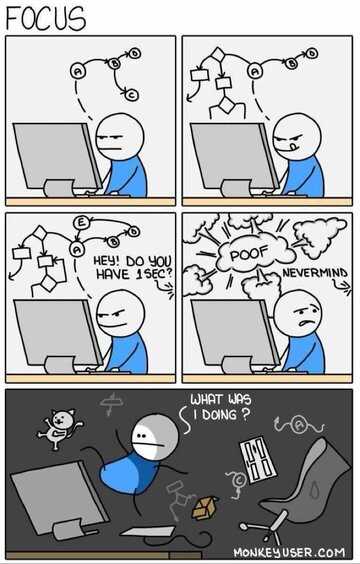

It’s no surprise then, that there are so many memes and comics out there showing developers suffering from interruptions and context switches.

Every single developer will tell you that getting interrupted in the middle of a task is an absolute productivity killer. And it’s not just a theoretical problem. Our recent Livecycle Collaboration Study found that nearly 50% of developers are actively struggling with this problem in their current workflows.

Having studied dev-team collaboration for the better part of the past year as head of Product Marketing at Livecycle, it’s amazing to me that in this regard, the system is basically set up to fail.

Take the following sequence of events for example, which illustrates a common workflow dilemma that many developers face:

- Developer works on Task 1

- Developer completes the Task 1 and merges it so that other stakeholders can review

- Developer moves on to Task 2

- Review comments for Task 1 interrupt the developer’s current focus on Task 2

- Developer context switches from Task 2 back to Task 1, which affects the quality and schedule of both tasks

It’s the ultimate can’t live with ‘em, can’t live without ‘em scenario.

On the one hand, developers must have the flexibility to focus on their current task. On the other hand, the completion of any given task requires subsequent reviews by other stakeholders. These reviews often translate into comments, questions, and ultimately unexpected interruptions for the developer who has since moved on to another task or project.

And this is just one of the many workflow scenarios that play out every day and similarly impact developer productivity and output.

An issue that affects the entire company

It’s important to recognize that although the developers are the ones complaining about it, it’s not just exclusively their issue. In this case, the developers’ problem is - by extension and by definition - a problem for the product and the entire company.

In fact, according to data from a recent McKinsey study, removing points of friction from the development workflow to enable a higher “developer velocity” directly and positively impacts the bottom-line success of businesses across all vertical markets.

So this is not just a problem for developers. This is a fundamentally important issue for all dev teams and businesses to confront head-on.

Half-Baked “Solutions”

The half-baked “solutions”

For an issue that is so widey felt by developers and development teams, and so broadly discussed in dev-centric and productivity-oriented literature, we’d expect to find some sophisticated solutions out there. But surprisingly, the best that the industry has been able to come up with thus far are fancy ways to basically shug shoulders and say: “it is what it is”.

I recently found a telling list of concrete suggestions in a Reddit thread asking about ”Developer context switching - tips & tricks”. These are the kinds of suggestions that came back from the crowd:

- Aggressively book blocks of focused work time in your calendar

- Turn invisible in slack, close down email, etc

- Turn off audio notifications in Slack

- Use the “StayFocused” chrome extension to block every social-media/etc website

- Use Brain.fm for very good focus music.

- Create “no meeting” days

- Read productivity books like Getting Things Done

All of the above suggestions do a disservice to developers and dev teams in that they assume that we need to live (and work) in a constant state of tension. These approaches imply that developers will always need to context-switch whether they like it or not. And as a result, each and every one of these suggestions is more of a band-aid that stops the bleeding than a comprehensive solution to the actual problem.

There has got to be a better way to handle this.

Taking a step back to understand the problem

If we’re going to have any chance of actually addressing this problem, we need to take a step back to better understand what is causing the problem in the first place.

And to better understand the root cause of the issue, let’s borrow the “maker vs. manager” framework made popular by Paul Graham in a blog post from 2009.

Paul writes as follows:

“One reason programmers dislike meetings so much is that they’re on a different type of schedule from other people. Meetings cost them more.

There are two types of schedule, which I’ll call the manager’s schedule and the maker’s schedule. The manager’s schedule is for bosses. It’s embodied in the traditional appointment book, with each day cut into one hour intervals. You can block off several hours for a single task if you need to, but by default you change what you’re doing every hour.

When you use time that way, it’s merely a practical problem to meet with someone. Find an open slot in your schedule, book them, and you’re done

Most powerful people are on the manager’s schedule. It’s the schedule of command. But there’s another way of using time that’s common among people who make things, like programmers and writers. They generally prefer to use time in units of half a day at least. You can’t write or program well in units of an hour. That’s barely enough time to get started.

When you’re operating on the maker’s schedule, meetings are a disaster. A single meeting can blow a whole afternoon, by breaking it into two pieces each too small to do anything hard in. Plus you have to remember to go to the meeting. That’s no problem for someone on the manager’s schedule. There’s always something coming in the next hour; the only question is what. But when someone on the maker’s schedule has a meeting, they have to think about it.

For someone on the maker’s schedule, having a meeting is like throwing an exception. It doesn’t merely cause you to switch from one task to another; it changes the mode in which you work.”

According to Graham, the makers and the managers operate on two completely different wavelengths. And trying to mix the two is a recipe for instant tension and friction.

We can use these same categories to understand the inherent issue with context switching.

When another stakeholder approaches an active developer with a question, or a review comment on a previously submitted task, the two colleagues might be involved in a single conversation, but they are certainly not speaking the same language.

The person interrupting the developer is operating in “manager” mode. There’s a specific task or question that needs to be dealt with in a vacuum. It’s just another item in a lost checklist of tasks to complete before the end of the sprint.

For the developer, however, this context switch represents a fundamental shift from maker mode to manager mode. And it is this jump (and its lingering effects) that causes all of the personal, professional, and technical tension that we end up laughing about in those industry-joke memes.

The ‘manager mode’ approach

The maker vs. manager framework gives us better context to understand the inherent shortcoming of the band-aid solutions we summarized above.

All of these suggestions attempt to take the developers out of their natural “maker” state and force them into “manager” mode to complete the process.

These approaches accept that developers will have to toggle between maker-mode and manager-mode throughout the workflow and it will probably come at a cost. And so, the strategy becomes finding ways to limit the effects of this sub-optimal reality with some surface-level productivity hacks and scheduling practices.

The ‘maker mode’ approach

The beauty of the “maker vs. manager” framework is that it allows us to explore a fundamentally different approach to addressing the issue. By breaking down the issue to its simplest terms, we can cut out the noise of habits and common practices to re-ask the simple questions and explore better solutions that are hiding in plain sight.

If the root of the tension around context-switching is in that we are shifting developers out of their preferred “maker mode” to an undesirable “manager mode”, then it would seem obvious that a better solution would be to find ways to keep developers in maker mode throughout the entire workflow.

So what might a maker mode approach look like?

A maker mode approach to this issue takes a step back to reassess the situation in a more holistic way. It assumes as a default premise that a developer should be empowered to maintain focus in “maker mode” as much as possible. This is the status quo that should be maintained. If any part of the workflow is to be modified in a creative way, it should be the way that we gather and process feedback from the other stakeholders. After all, these stakeholders are already used to operating in manager mode to begin with, so shifting their engagement slightly within the existing manager mode context is a far easier ask than expecting developers to transition all the way from makers to managers.

Perhaps there are ways to include these other “manager mode” stakeholders in the review process in a less intrusive way, to collect and deliver their feedback to developers without needing to interrupt the developers’ current focus.

An example of the ‘maker mode’ approach

At this point, you might be rolling your eyes, Sure, this all sounds great, but good luck trying to make it happen. All we need to do is find a way to get other stakeholders involved, gather feedback and questions and get developers to address them without needing to interrupt the developers from the deep work that they are currently involved in.

But the truth is, although this sounds like a tall order, there might not be a need to reinvent the wheel to achieve this. Perhaps we can simply leverage the tools already at our disposal to allow everyone on the team to do what they wanted to do in the first place.

Let’s keep thinking outside the box to imagine one way we might get this done.

A more inclusive pull request

One of the tools already at the disposal of developers is the “Pull Request” (PR). For all intents and purposes, each Pull-Request is opened by a developer as the ‘ready for review’ moment. By opening a pull request, developers are actually asking for feedback from their peer developers before they merge the code changes back to the ‘main’ branch. The pull request is key in that it is the mechanism for collecting feedback that developers are already used to.

Although the PR has historically been a dev-centric utility, imagine if we took the opportunity to piggyback on this moment in time to somehow include all relevant stakeholders in the review process. Maybe we can use this more natural invitation for feedback to absorb potential future interruptions from other, less-technical stakeholders as well.

Now, I know what you’re going to ask me. The pull request is just a bunch of code! How the heck can we use it to get other people involved who may not even have a Github account? How can the designer and the marketeer use the PR as a question and feedback mechanism?

Well, what if the PR wasn’t just a bunch of code? What if it had a visual layer that would level the playing field for everyone? If every PR automatically come with an accompanying isolated preview environment, it would enable practically anyone on the team to experience the latest changes on their own at that critical stage of the review process.

A more collaborative pull request

Building and hosting a representative version of the code change and sharing it with more stakeholders could be the first critical step to a more inclusive pull-request-oriented workflow that simultaneously includes others while freeing developers to work on other tasks.

But it’s only a first step.

Because, to really address the context-switch issue, we need to not only give other stakeholders access to the PR, but also to collect their feedback and comments in a more optimized way.

And so, what if this PR preview environment wasn’t “view only”? What if it was an active ‘playground’ that allowed each collaborator to leave comments on top of the playground UI itself? In this way, all relevant collaborators would be able to leave clear comments on the latest code change in their original context, on top of the product UI.

By empowering other stakeholders to join the PR review process and by enabling them to asynchronously leave comments for developers, we could free the code owner from the burden of unnecessary interruptions so that they can review and address the questions and comments when they are ready to do so.

Using this new “maker mode” approach, the problematic workflow we outlined above would now look something like this:

- Developer works on Task 1

- Developer completes the Task 1 and merges it so that other stakeholders can review

- Developer moves on to Task 2

- Review comments for Task 1 are collected instantly and asynchronously and they DO NOT interrupt the developer’s current focus on Task 2

- Developer can complete Task 2 (or break at a logical stopping point) and shift focus to address all Task 1 issues at a time that makes sense

And more generally, a more inclusive and collaborative approach to PRs would offer teams a number of immediate benefits:

- Reduce context-switches → Once you merge your feature branch you can actually move forward to your next task once and for all.

- Instant review gathering → Control and Invite the feedback whenever you need it (just as you do with peer developers when asking for code review)

- Reduce ambiguity of branches and maintain a clear Git structure

- Automatically create an audit trail for all needed feature changes by all stakeholders in the company

- Always on reproduction environment for every commits → Making your SCM an application time machine.

There’s always room for creative solutions

This exercise is a good reminder for me that there is always room to think creatively and come up with novel approaches to solve problems. Even (or perhaps especially) if those problems are long-held industry assumptions. When someone says “this is just the way it is” or “this is the way we’ve always done things”, that’s another way of saying: “there’s an opportunity to come up with a much better approach to this”.

In the case of developer workflows and context-switching, perhaps the biggest benefit to our proposed “maker mode” approach is that it simply preserves (and amplifies) the natural state of each of the participants. Coders can focus on coding. Other stakeholders (who are perhaps more oriented towards the “manager” way of doing things) can focus on completing their reviews better and faster. And everyone involved does their work asynchronous, eliminating those unnecessary interruptions and context switches.

So effectively, with a little creativity, maybe our “PRs” can become “PRty”s that everyone is invited to so that everyone on the team can do more smiling and more coding, and less stressing and complaining.